Living Archives: The Challenge of Capturing Memory in a Photographic Project

Edine Célestin

→

(Kolektif 2 Dimansyon - K2D)

Quand un ancien meurt c’est tout une

bibliothèque qui brule.

The proverb cited above by and often attributed to to Amadou Hampâté Bâ addresses the transmission of knowledge, memory, and traditions. It also encapsulates the experience of my colleagues Fabienne Douce, Réginald Louissaint Junior, Moïse Pierre, George Harry Rouzier, Mackenson Saint-Felix and I during our research in Kazal. As photographers from the first post-Duvalier generation, all part of the collective Kolektif 2 Dimansyon (K2D), we spent four years working together on an archival project that traced memories of François Duvalier’s dictatorship in Haiti.

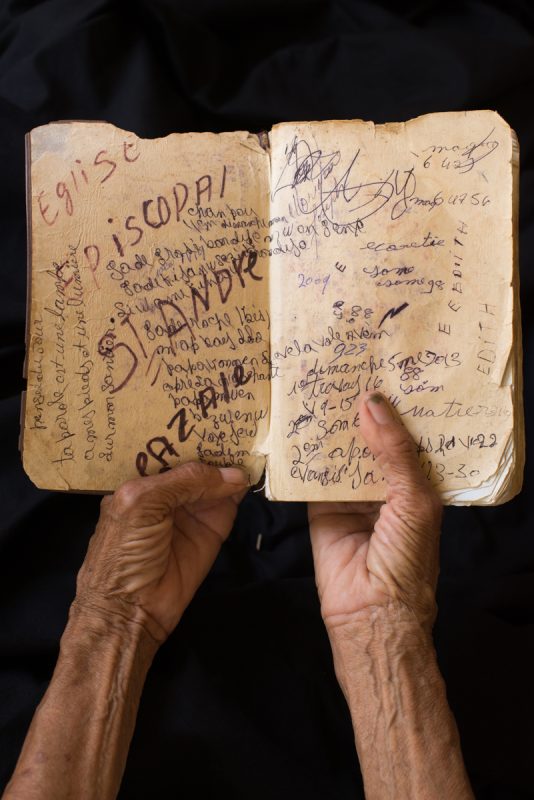

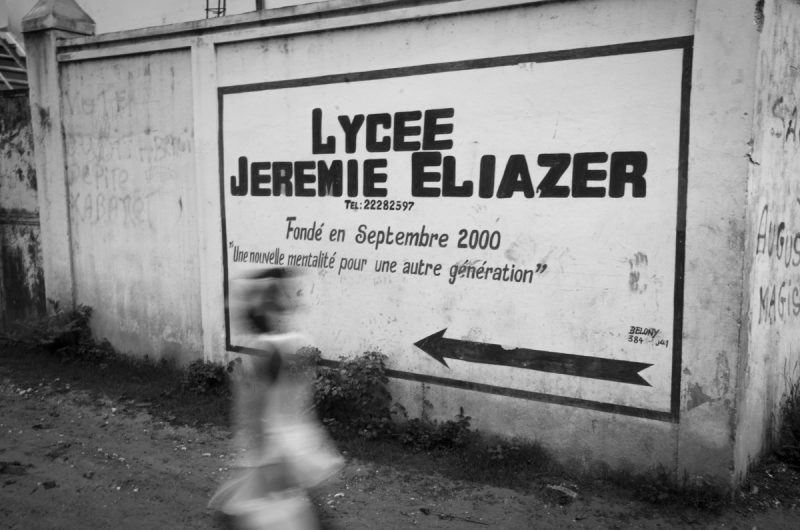

Our research entitled “Kazal: Memories of a Massacre under Duvalier: A Photographic Approach” focused on Kazal, a village located north of Port-au-Prince where, in the spring of 1969, Duvalier’s military and militia crushed an uprising of local peasants who were protesting abusive taxes and fighting for the right to draw water from the river that ran through their village. The ensuing hostilities lasted from March 27th to April 16th and resulted in the death of at least 23 peasants, the disappearance of another 80, and the destruction of 82 houses. These numbers are approximate; we will never know exactly how many people died, how many houses were destroyed, or how many women were raped. Only rare material traces and a few witnesses to this historical event have 27 resisted ruin and time. During the dictatorship, the Macoutes (militias) burned down homes, destroying all reminders of their victims, and people could not afford to keep their memories for fear of reprisals. Afterwards, many of the objects and photographs that brought back these events were so painful to hold on to that surviving families destroyed them.

At the beginning of our project, we ran around in circles trying to find people who might have archives, and we treated the few objects we were able to find like treasures. Eventually we realised that what we were looking for was already in front of us: we had to work with people, their memory, their recollection of the facts. Our archives were these people. Haiti has a very strong oral tradition, and 20% of its population was considered illiterate in 2020, so here archives take on another dimension: they are alive, they are human, they are preserved in our memory. They are memories we cherish or pains we would like to forget; a difficult past to reckon with, or a story too strange to tell.

In her research on Dakar, Marie Gautheron describes the “living archive” as a form of cultural heritage. In this context, the living archive is linked to intangible heritage and is comprised of “the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge and know-how—as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated with them—that communities, groups and, where appropriate, individuals recognize as part of their cultural heritage” (Gautheron 9). Haiti has experienced—and continues to experience—numerous political crises, wherein goods, cultural practices, objects, and homes are continuously destroyed. Yet peoples’ memories survive despite everything, and they are preserved and passed on in the form of stories, such as the ones my grandmother told my mother, who told them to me, and that I will tell my own children. Therefore, in Haiti, bearing witness and caring for “living archives” takes on a fuller meaning: our archives are our people, who carry within them the joys and pains of history.

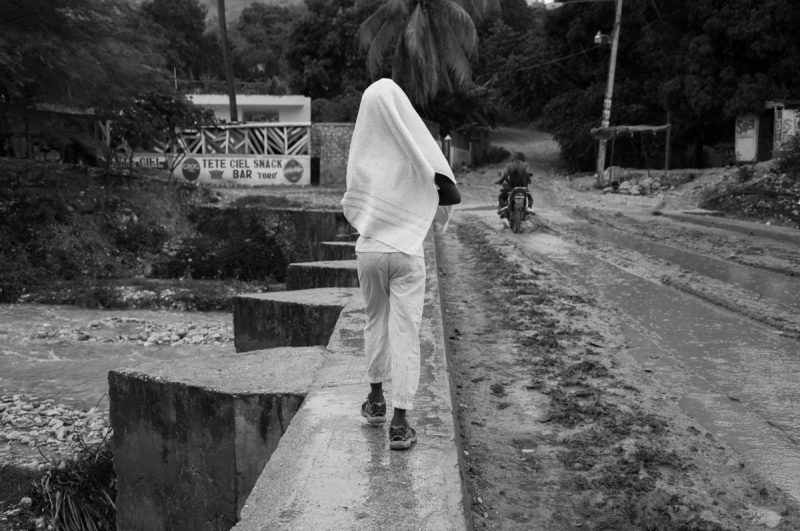

As photographers, we asked ourselves how we could hold these memories, testimonies, and recollections. For us, photography was first and foremost about informing, documenting, and bearing witness to a given reality. The documentary approach we used for the Kazal project was totally new to us: we now had to conduct interviews, research sources, and work in the field to create a continuous dialogue with our subjects. This was at times uncomfortable: as city-dwellers from the capital, meeting the inhabitants of Kazal—most of whom are peasants and farmers of the land—we were forced to confront social, cultural, and geographical barriers. Despite these difficulties, our unwavering determination to return to the same places and people—to listen, to show, to share—opened new lines of research, new images, new ways to circulate memory. As Édouard Glissant explains, it is through “relation” that new forms of lucidity emerge. If we want to share the beauty of the world, if we want to stand in solidarity with suffering, we must learn to remember together, across the fractures of history and memory.

Our research in Kazal was forged through ongoing relations with residents between 2015 and 2019. We developed a deep bond with the people of Kazal, building trust over the years and through the possibility that documentary photography offers to evoke memories from elements of everyday life. The medium of photography can recount memory alongside more ancient forms of storytelling such as oral narration, writing, and so on. Photographs are also material and, as a form of testimony to the past, they can reactivate past memories and invite reflection. However, they offer only fragmentary, partial, and subjective testimonies that tell us “as much about the subject as [they do] about the photographer” (Lo Calzo 168).

The result of our project designed to shed light on the period of the dictatorship is at once a book, a travelling exhibition, and a long-format website funded by the Haitian Foundation of Knowledge and Liberty. The testimonies gathered online and in the book, along with the photographs that were taken as part of a master class run by Nicola Lo Calzo and coordinated by Maude Malengrez, are articulated in the present tense. Carefully framed and captured, and produced through dialogue and reciprocity (Girola), the images of people, tools and of the trees that protect Kazal prolong every word of reminiscence expressed about the village’s traumatic past. Reflecting the villagers’ testimonies, and with the aim of transcribing keywords that recur in their speech, we divided the project into five chapters: Dlo (Water), because water was one of the elements that triggered the massacre; Latè 31 (Land), because Kazal’s inhabitants were mostly peasants who worked the land; Mystik (Mystical); Letat (State or Government), because the victims have been forgotten by the State; and Memwa (Memory) to refer to the memory of people, places, and events.

We’ve included here some images from the project, but invite you to take a richer tour of Kazal: Memories of a Massacre under Duvalier: A Photographic Approach on www.memwakazal.com.