Verloren Banden: Moluccan Footage, Articulating Perspectives in Postcolonial Netherlands

Jeftha Pattikawa

→

(Verloren Banden / Nationaal Archief)

I was born in a Moluccan barracks camp in Vaassen, a village sixty kilometers from Hilversum. That same year the Netherlands was startled by a series of dramatic events: young Moluccans took hostage of a primary school in Bovensmilde and hijacked a train near De Punt. Two train passengers and six Moluccan youngsters were killed during a violent attack by the Marines. The Moluccan community at that time lived at odds with the Dutch government. Nineteen seventy-seven was the peak of a radicalization process that had begun in the mid-1960s. These Moluccan youth protested against the bad way their parents were treated.

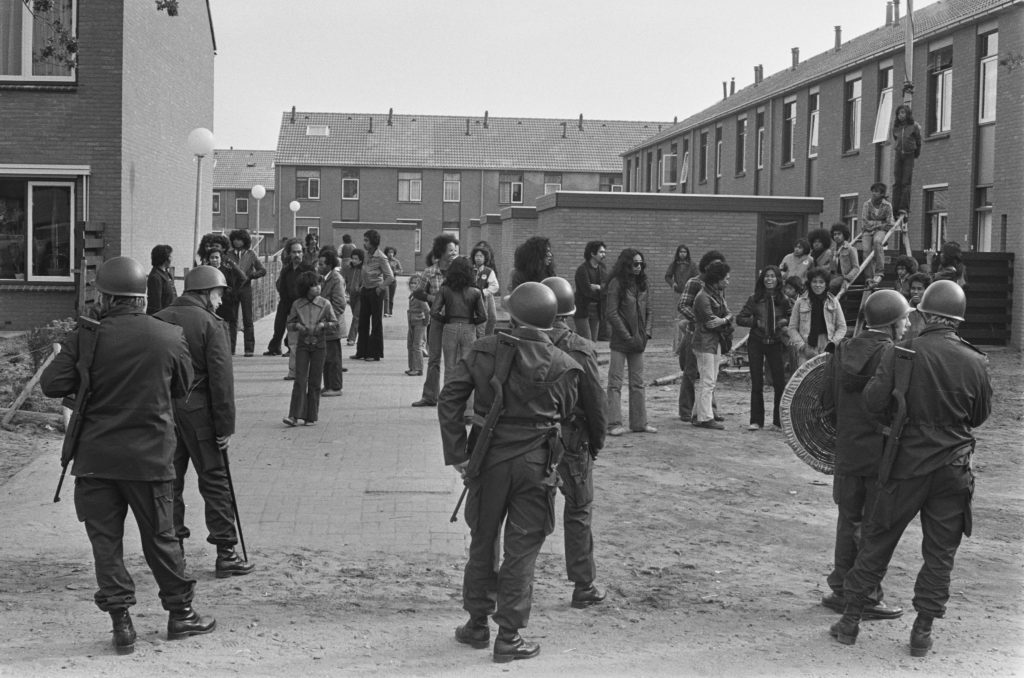

The position of Moluccans in the Netherlands is influenced by colonialism. After arriving on military service order to the Netherlands in 1951 due to the decolonization process of Indonesia, the Moluccan community was housed in camps. Later, they were housed in special residential areas. Living in the camps and the special neighbourhoods resulted in the social isolation of Moluccans in the Netherlands, causing serious socio-economic disadvantages. This isolation was further reinforced by the Moluccan community being focused inward on their own Moluccan republic. The image of Moluccans in the Netherlands was formed by resistance, protest, radicalization, and violence. Just before my year of birth an event took place that caused a deep wound in the local Moluccan community in Vaassen; an event that lasted two days, but has always stood in the shadow of a series of dramatic events that took place in the 70s. On October 14, 1976, the violent evacuation of a part of our barracks camp took place, enforced through (state) violence. The demolition had been planned for some time, but some families, including mine, refused to leave that part of the camp. The situation was even more complex because a new residential area built on the same site and that we were to move into, would replace the barracks camp.

There was a rumour circulating in the intelligence service that heavy weapons would be present in the camp. During the forced eviction, the government decided to deploy a large police and military police force. The residents of the camp heavily resisted when the police entered. That day, many innocent families lost their barracks and personal belongings. The heavy weapons that were supposedly there, were never found. After this traumatic event, the community became even more closed. Distrust of the government grew and within the enclosed community unemployment and drug abuse among young people increased explosively. Of the estimated 1,100 inhabitants, 150 became addicted to hard drugs.

In September 1978, young Moluccans from the local community set up a welfare organization specially for Moluccans in Vaassen. This foundation, called Waspada—translated as “be alert and vigilant”—was created because there was no specific drug shelter for Moluccan addicts and unemployed, and because the existing Dutch drug help organizations were not able to reach the Moluccan youngsters. Many of the Moluccans using hard drugs felt uncomfortable and misunderstood by Dutch society. The young people had to find their own way and create their own tools to help their community, and to become a full part of broader society.

During this period, more welfare organizations specifically for Moluccans were set up by Moluccans in the Netherlands. Professor of Moluccan migration and culture Fridus Steijlen wrote about this in his co-authored book with Henk Smeets In Nederland Gebleven [Stayed in the Netherlands]: “The increasing use of hard drugs within the Moluccan community intensified in the mid-1970s. Subsequently, from 1977, around fifteen projects were created to help Moluccan hard drug addicts […]” (298). Dutch institutions were not aware of these problems among Moluccans. From the late 1970s, the Moluccan community in the Netherlands took the initiative to tackle the socio-economic problems themselves, specifically concerning drug use and the high unemployment rate. Thanks to these initiatives, which were a strong sign of the resilience of the Moluccan community, the problems would eventually be overcome, after which the Moluccan community could fully participate in Dutch society.

Back in the village of Vaassen during this period, various activities for young and old were developed by and under the umbrella of Waspada. In addition to the drug aid, there were sport and music activities, a printing company, and a video group. With video being a new medium of the time, one of the activities initiated was a video workshop. The film project named Cermin, which means mirror in Moluccan Malay, ran from the end of the

70s to the mid-90s.

In 2016, forty years after the evacuation of our barracks camp, I found an old photograph of young Moluccans with professional video equipment in a family photo album.

After an intensive search for these Moluccans with the video camera, I ended up in the attic of a former member of the video group where a treasure was waiting for me: more than 300 professional tapes with a total playing length of 144 hours consisting of Waspada footage showing the Moluccan perspective. This footage makes us part of intimate conversations between generations that had to find a new place. It shows daily life. It shows how we danced and made music. It shows traditional weddings, how families expanded, and how we celebrated for days. On the tapes one can hear how the Moluccan Malay language became more and more entangled with Dutch as time went on, and how it eventually faded. The footage is about day-to-day routines within the community.

With a few core members of the video group—the makers of the footage—we investigated options for safely housing these valuable tapes. Of course our first option was the audiovisual archives of the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision. Unfortunately, we were rejected, the argument being that the institute already had enough material about Moluccans.

Together with the support of the local Moluccan community we took the initiative to digitize some of the tapes and organize exhibitions by ourselves. We mobilized the former residents of the barracks camp and many other Moluccans through walks, exhibitions, and during informal meetings in the living rooms of our community. Near the places where Moluccans used to be temporarily housed in the barracks camp, there are now residential areas where Moluccan families still live. These neighborhoods in the Netherlands have become a lieu de mémoire, places of remembrance for the community.

On Saturday, October 22 in 2016 we organized a walk to Vaassen; with a large group of people, we brought the videotapes back to the community. That day hundreds of people were waiting for us with the sound of the tifa drums and Moluccan songs. There were children and grandchildren of the first residents of the barracks camp; everyone joined. Our story was covered by the media and through the councilor of the municipality the footage has now found a place at the Gelders Archief. This means that the tapes are now being digitized in collaboration with this regional historic center, with the local Moluccan community providing the metadata and descriptions.

With their cameras, the Moluccan youth back then unconsciously recorded the period of growth and resilience of the community; it is a small and local history, but represents a larger Moluccan perspective. Archives are the foundation for the great historical stories that we tell. Unfortunately the stories of Moluccans as loyal fearless soldiers in the service of the colony, and the violent “other” in the 1970s, still dominate the archives. These stories that pervade the archives tell how Moluccans arrived, were tucked away in barracks on the outskirts of society, and radicalized. But what happened next? And what happened after a large part of that generation became addicted and unemployed?

The footage shows how we organized ourselves, out of view of the media and memory institutions. And how, despite marginalization, isolation, and the resulting social problems, found a way to participate in Dutch society—from exile to migrant to citizen. The footage is unique in two ways: the images of Waspada show the resilience of the Moluccan community in postcolonial Netherlands, and the visual material was made by the community itself.

The importance of self-representation is best explained by the words of the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in her TED presentation called The Danger of a Single Story. Here she speaks of what happens when complex human beings and situations are reduced to a single narrative. She says:

Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity. […] It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power. […] Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story, and to start with, “secondly.” Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story.

In the Moluccan case, start with Masohi and Muhabbat or our Adat, the Moluccan traditions and rules of life that often formed the foundation of the Moluccan welfare organizations in the Netherlands, and not with the dramatic events of the 70s or the recruitment of Moluccans as ethnic soldiers in the colonial army, although these stories still dominate the archives. And

you have a completely different story.