The Wendy Clarke Collection: Love and More in the Archives

Mary Huelsbeck

→

(University of Wisconsin-Madison)

Expressions of love and compassion can be found in many places in an archive. Personal letters, diaries, postcards and greeting cards document how love and compassion have been articulated over many years. But these written expressions can sometimes be misconstrued or misinterpreted due to language differences and changing societal norms. Oral histories and home movies enable viewers to see and/or hear moments of romantic, platonic or familial love as well as celebrations and stories of lost love and heartbreak. Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes project (1977–2001) and other of her video art projects are a unique primary source that capture some of the many facets and meanings of love and compassion.

A video art project, the Love Tapes was open to anyone who wanted to participate—it had no age limit, no admission fee and no censoring of comments. Participants came from many ethnicities and countries and could speak in whatever language they wanted to. Money or social standing did not matter. Members of the gay, lesbian and transgender communities were welcome. Love Tapes was recorded at the World Trade Center in New York City, at museums, in prisons, at a shelter for battered women, at youth centres and colleges, at centres for senior citizens and for people with disabilities across the United States, in France, Brazil, Mexico and even in a van that travelled the streets of Chicago. The thoughts and insights shared by the people who recorded their Love Tapes were generally unrehearsed and unpolished and blended joy and sadness, sharing both anecdotes and raw emotions. The participants occasionally invoked clichés, but more often they stumbled toward the words that would adequately capture feelings, memories, presence and loss.

Wendy Clarke is the daughter of independent filmmaker/video artist Shirley Clarke. Starting in 1969, Shirley began experimenting with video— specifically the Sony ½” open reel videotape format. The introduction of the affordable and portable ½” open reel videotape in 1969 made it possible for many artists, schools, non-profit organisations and other non-professional consumers to record and create their own content. Shirley, along with Wendy, Bruce Ferguson, Dee Dee Halleck and Andy Gurian and others, formed the TP Videospace Troupe. At the Chelsea Hotel and various museums, community centres, colleges and universities along the East Coast, they gave workshops demonstrating how video could enable people to be both creator and audience.

In 1972 Wendy began a personal video diary that she used “as a tool for expressing my true feelings, needs and wants, and to see if I was being honest” (Clarke 101). She added to her video diary for the next five years. In 1977 she decided as an experiment to “talk to myself in my video diary for as long as it took to say everything I was feeling at the time, until I had nothing more to say” (Clarke 101). The result was three successive 30-minute tapes. Sensing that she had captured something special, Wendy chose to share the tapes and invite feedback from a few trusted friends. This led her to publicly share one of the tapes, entitled “Chapter One”, as part of the Interactive Video exhibition at the University of Southern California at San Diego’s Maderville Art Gallery. Inspired by the long comments left in the guest book by visitors expressing their own feelings about love, Wendy shared “Chapter One” with some of Shirley Clarke’s video graduate students at UCLA, which led five of them to create their own tapes. The format for the Love Tapes was a result of this session with the UCLA students: people watch other people’s “love tapes” and then record their own, sitting in a booth or a room with a camera and monitor that allows them to look at themselves as they talk for three minutes about love. The three-minute time limit was chosen because it is the duration of the song “I’m in the Mood for Love”, which was used at the UCLA session; as the Love Tapes evolved, participants could choose from a long list of songs and a variety of different backgrounds. Participants viewed their tape after recording it and decided whether to have it erased or to sign a release to have it added to the collection.

Between 1977 and 2001, over 2,500 tapes were made around the world, illustrating the vast range of interpretations, meanings and memories prompted by the word “love”. Through this process, Wendy found that video can operate both as an apparatus for intimacy and as a facilitator for self-examination. The project’s breath-taking scope revealed a rare glimpse of humanity communing through shared experience, albeit mediated by video technologies of both recording and exhibition. Released on PBS and other public television stations in the 1980s, the Love Tapes marked a milestone for the advancement of the video medium. Wendy’s work was visionary in anticipating the kinds of mediated interactions that became increasingly common on internet platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.

The Love Tapes is also a time capsule that documents how a wide range of people—from a four-year-old child to senior citizens—feel about love. The breadth of representation in the Love Tapes is remarkable in bringing people together in the 1970s and 1980s to describe what love meant to them. Love Tapes has been exhibited extensively around the world since 1980, including in shows at the Museum of Modern Art (1980), the World’s Fair in New Orleans (1984), on KCET/28 TV in Southern California (1989), as part of a Wendy Clarke retrospective at Anthology Film Archive in New York City (2001) and most recently at LUX Moving Image in London, England (2019).

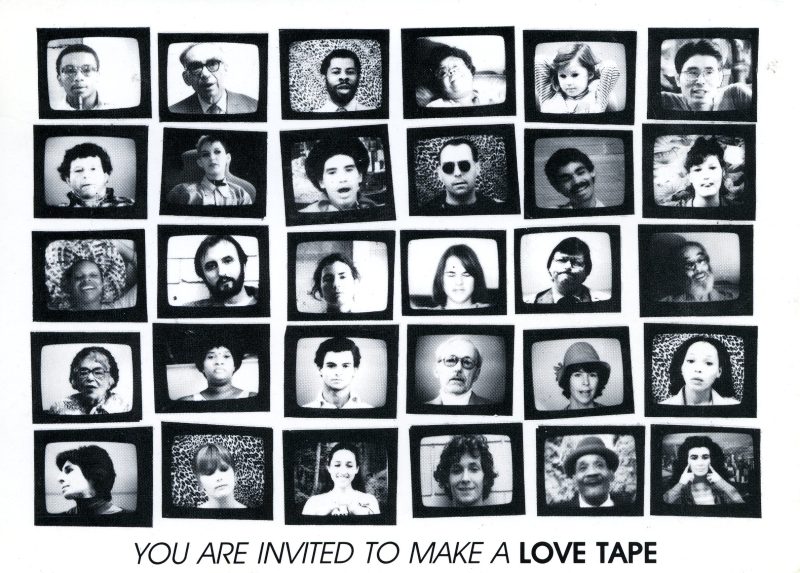

Love Tapes recorded at the World Trade Center in New York City in April-May, 1980. Credit: Wendy Clarke collection, WCFTR

To date, approximately 200 Love Tapes have been digitised—most from the event at the World Trade Center in New York City in April and May 1980; of these, I have watched approximately 40. With every Love Tape I watch, I am struck by the honesty, genuineness and thoughtful insight that participants share. People admit that while they’ve never lacked love in their life, they are afraid of it, or they don’t know what love really is, or they take it for granted. A man who had broken up with his girlfriend the day before is defiant, saying that love is a “two-way street” —he felt his girlfriend was using him—and proclaims that he is “a human being; I have feelings.” A woman wants to learn to love unconditionally like her grandmother, who, at age 77, had decided that it was a waste of time to deal with negative emotions. Another man, wanting to be an artist, feels that before he can do anything in his life he needs to learn not only who he is but also how to love himself. For another woman, recording a Love Tape is an opportunity to tell her husband how much she loves and appreciates him—things she admits she could never say to him in person. When finished, many participants wonder if what they had said was good enough. Some express how much they enjoyed the experience. Others express a sense of relief at the three minutes being over and a feeling of accomplishment at having done it, while for others, three minutes was not nearly enough time.

Watching the Love Tapes, for me, brings to mind many questions. Would I be able to record a Love Tape—and if I did, what would I say about love? What do I know about love? How do I feel about love? And why do people say things—admit their feelings and fears—on tape that they could not say otherwise? What is it about the experience of talking to themselves in a booth for three minutes that gives them the courage and freedom to be so honest with themselves? It takes confidence – whether you think you have it or not—and some bravery to commit personal reflections to tape and then agree to share yourself with the world.

The Love Tapes and Wendy’s other video projects are powerful works of art but are also anthropological studies and oral history compilations. Wendy took a very personal exercise, one that had helped her process many emotions and aspects of her life, and invited everyone to participate and explore their senses and definitions of love. Instead of prompting responses using specific questions, she gave everyone the power to decide what to share and how to represent themselves. Unlike written documents, video recordings capture people’s thoughts and emotions with little ambiguity— unless they wish to be ambivalent. Words on a page can be impactful, but hearing and seeing people smile, laugh, cry and struggle for words as they talk about love adds a very particular embodied layer of emotion for the viewer to experience.

Wendy believed that everyone could make art and that video could connect people from around the world. Her video projects are an amazing collection of art that inspire, fascinate and challenge the viewer on many levels. They are also a unique resource that can be used by scholars of many disciplines, along with other archival collections, to gain insight into what people from a specific location and at a specific point in time thought about love. The Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research (WCFTR) is privileged to be the home of the Wendy Clarke Collection.