The Museum Visits a Therapist

Mirjam Linschooten

→

(Visual Artist)

Sameer Farooq

→

(Visual Artist)

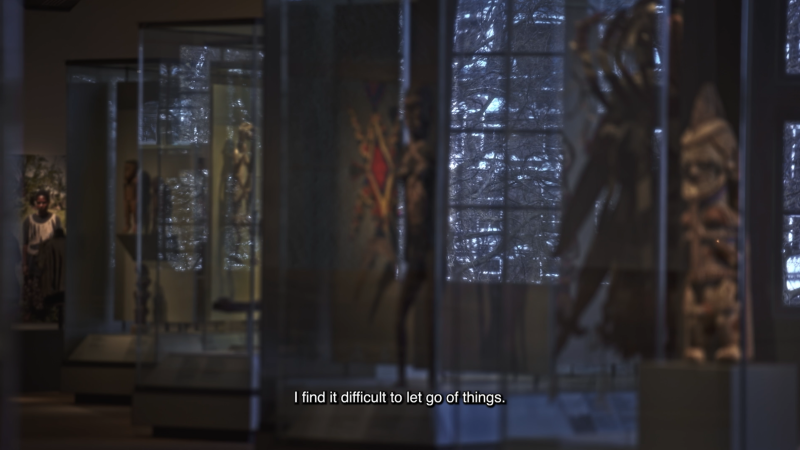

For over a decade we have been engaged with the fraught and violent histories of encyclopaedic museum collections, their colonial origins and structures. Our works are often collaborative and counterbalance how dominant institutions speak about our lives: a counter-archive, new additions to a museum collection or a buried history made visible. Over the last four years we have brought our research to the largest ethnographic museum of the Netherlands—the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam—where we produced the experimental film The Museum Visits a Therapist.1 We started by researching the Tropenmuseum’s collection and exhibition history, and in 2018 we were granted the opportunity to film at the museum during restorations and the construction of a new permanent exhibition.

As the Tropenmuseum holds many looted objects, we began to draw parallels between centuries of unresolved colonial trauma and the physical patterns we filmed in the museum. The project started from these observations, seeking to understand how the inherited trauma of Dutch imperialism has found its way into every aspect of the muse um’s construction and operation.

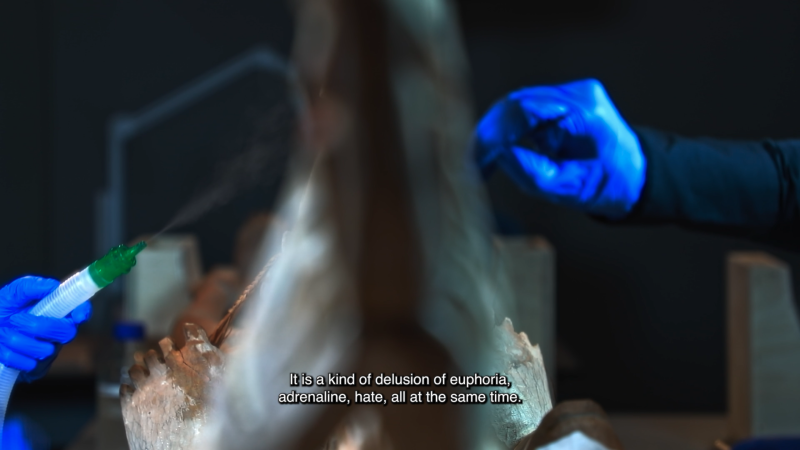

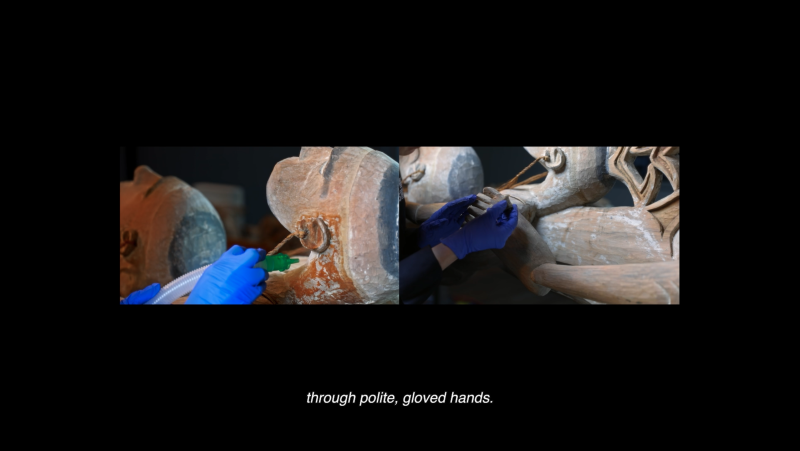

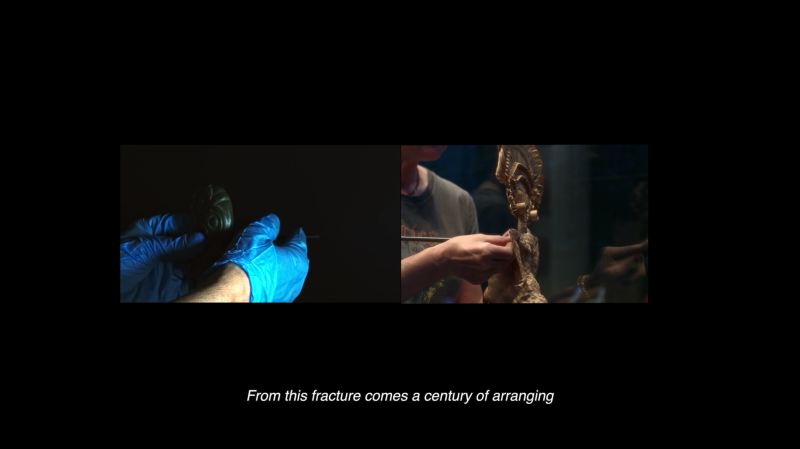

The first period of filming was largely about watching what was happening. While observing, we noticed some curious tendencies and gestures that we thought were interesting. Objects were obsessively cleaned, trembling hands repaired and braced artefacts and displays were arranged with an obsessive precision. Reviewing our footage, we found several similarities between museum practice and the cognitivepsychological symptoms of trauma, including obsessive-compulsive behaviours and shame. Obsessivecompulsive disorder (OCD) is a common disorder in which a person has uncontrollable obsessions and/or behaviours with a repetitive urge.

We wanted to understand the roots of this behaviour and show where these gestures originated. In his book The Brutish Museums: The Benin Bronzes, Colonial Violence and Cultural Restitution, curator Dan Hicks writes:

Through a camera, through a museum display, through a gun that shoots twice, an event, through violence, can encompass a kind of fragmentation that means it can’t quite end.

This quote spoke to us a lot, because it links what is happening in the museum today to the violence associated with removing objects from their original contexts. Not just physical violence, of course, but also the violation of appropriation: the violence that comes from feeling entitled to take things and put them on display. Further fragmentation happens when the objects are separated from these violent events and are placed in the context of care.2 While the violent history becomes detached from the collection over centuries, evidence of the theft and anxiety that gave rise to the museum are written on the architecture and in the gestures of the museum workers.

We connected with this history by diving into a specific period of accumulation. In the film we follow the restoration of a series of bisj poles from the Asmat people of Papua, a Dutch colony until the early 1960s. These objects were taken by Dutch collector Carel Groenevelt, who worked for the Tropenmuseum and for the ethnographic museum in Rotterdam—both of which are today part of the National Museum of World Cultures.

Our research led us to the late 1950s/early 1960s, when Groenevelt was collecting in Papua and the Dutch were about to lose the colony. Dutch missionaries had settled centuries earlier in Papua and paved the way for traders and collectors. As Indonesia claimed it as its territory, the Dutch sent military troops in an attempt to retain it. All of these figures form the ground of a collection such as that of the Tropenmuseum.

This was a turbulent time, full of violence, uncertainty and distress. In a letter from the museum to collector Groenevelt, we can sense the urgency the museum felt while collecting —or ‘grabbing’—as many objects as they could as the colony slipped away from the Dutch.

Honourable Sir Groenevelt,

In the area of Dutch New Guinea, we not only have the opportunity to have the most beautiful collection in the country, but also to get a collection of world reputation.

Here lies a big task!!!

Building a beautiful collection concerning our

New Guinea. So continue to grab what you can grab. The museum can use everything. (Hollander 65, translated from Dutch to English by the authors)

To evoke this history, we dug into the archives of these Dutch figures: stories from veterans,3 letters between Groenevelt and the museum and the diary of a missionary. We compiled the script from these journals, interviews and letters.

With this understanding of the inherited trauma of Dutch colonialism and how it has seeped into the gestures of workers at the Tropenmuseum, we wondered what would happen if the museum visited a therapist. The final film is structured as a conversation between a fictional therapist and the museum.

Our research led us to speak with therapists about different treatments and methods (Egan et al.; Fournier and Korteweg). For the film we used an intake questionnaire (Obsessive Compulsive Inventory – Revised, OCI-R), which is often used as part of an initial patient assessment. Our filmic language was also affected by therapeutic modes in its use of EMDR therapy (eye-movement desensitisation and reprocessing), where the patient recalls traumatic or distressing experiences while experiencing bilateral stimulation, such as side-to-side eye movement or a beeping sound moving from ear to ear. In the film we translated the formal qualities of this treatment into a filmic language expressed through a moving dot, sounds and flashbacks.

Offering a nuanced critique, The Museum Visits a Therapist navigates the history of violence, religion and trade that shaped the Tropenmuseum’s object collection and simultaneously imagines new forms of reparation within museum spaces.

___

AUTHORS’ NOTE

The following is a list of references that informed the making of our film

Attia, Kader. “Kader Attia speaks about the idea of Repair”. Youtube, uploaded by Judith Benhamou Reports, 22 May 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBYoL6z4V7Q.

___. “Scars remind us that our past is real”. Youtube, uploaded by Joan Miró Foundation, 15 June 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNnsNoDnQ9Q.

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. Verso, 2019.

Diyabanza, Mwazulu. “Experience: I steal from museums”. The Guardian, 20 Nov. 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/nov/20/experience-i-steal-from-museums?CMP=fb_gu&utm_medium=Social&utm_source=Facebook&fbclid=IwAR3aENMFBIS1yMOOlRdepODijS33Ad5vw5j1g6k2PUzt5w4Mr7LlkvgOM9g#Echobox=1605867157. Accessed 1 October 2022.

Eng, David L. “Colonial Object Relations”. Social Text, vol. 34, no.1(126), pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3427105.

“Fair Trade Heads: A Conversation on Repatriation and Indigenous Peoples with Maria Thereza Alves, Candice Hopkins, and Jolene Rickard”. South as a State of Mind, #2, Documenta 14, Kassel, 2016. https://www.documenta14.de/en/south/460_fair_trade_heads_a_conversation_on_repatriation_and_indigenous_peoples_with_maria_thereza_alves_candice_hopkins_and_jolene_rickard. Accessed 1 October 2022.

History of the Luseño People. Directed by James Luna, 1993.

Nichols, Robert. Theft is Property! Duke University Press, 2020.

Owoo, Nii Kate. Nii Kate Owoo on his film You hide me (1970)”. Youtube, uploaded by Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, 11 May 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W2EHjYjtdeg.

You Hide Me. Directed by Nii Kwate Owoo, 1970. Vimeo, uploaded by June Givanni Film Archive, https://player.vimeo.com/video/460714389?h=1e4330fb24.