“Looking Inward and Outward”: Confronting Silence in an Afro-Curaçaoan Archive1

Charissa Granger

→

(Erasmus University Rotterdam)

I think more than anything I was just trying to get

people to acknowledge how much of what we call

“Caribbean history and culture” is, in reality,

one vast silence.

—Junot Díaz2

Confronting Silence, Doing Wake Work

“We were never meant to survive” (Lorde)—neither were our stories of this survival. The Black archive is composed of silences, of unspeakable things unspoken (Morrison, “Unspeakable”). My first confrontation with this silence was personal, while working within my family archive to understand my matrilineal “afrosporic” (Philip 35) movements. Though able to go back six generations, dating back to the eighteenth century, birth dates are inaccurate, surnames are changed haphazardly for reasons unknown, and the migrations through the Caribbean islands that I was most interested in are unmentioned – Silence.

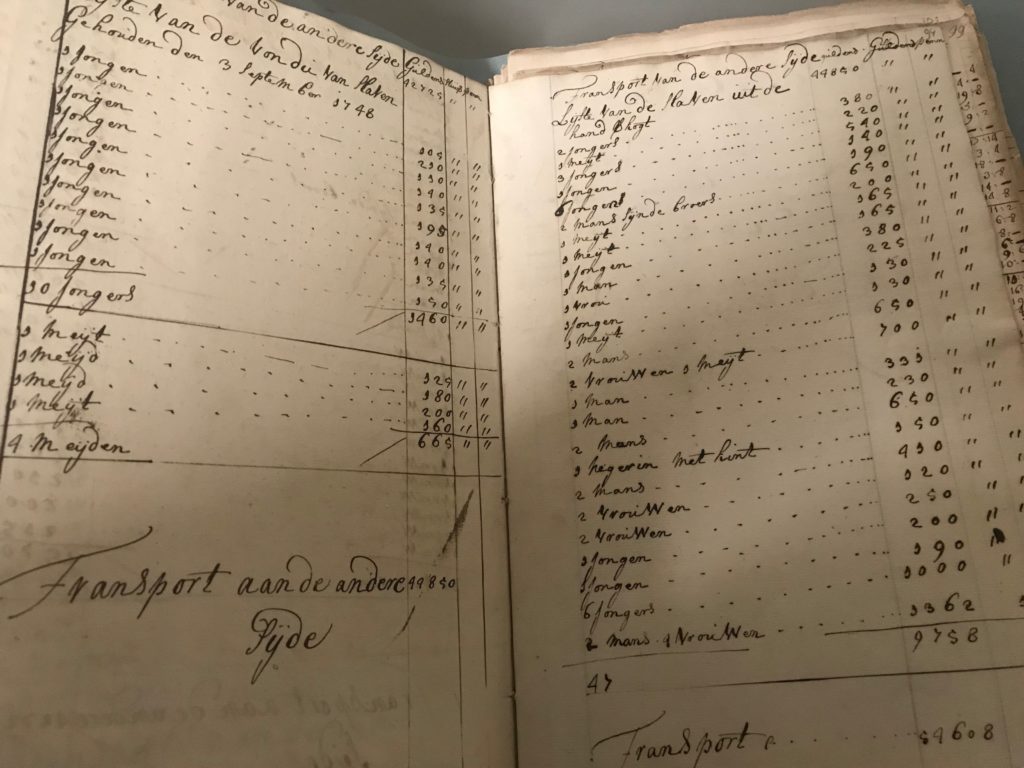

My second confrontation with silence was during a visit to the Zeeuws archive as in Middelburg. This archive concentrates predominantly on commerce; thus, the voices narrating the lived experience of Africans, names, and biographies of enslaved persons are unmentioned.3 Ship logs, detailing bills of sales and accountancy records of trades and names of slave traders are documented. “1 boy, 3 men and 1 negro woman with child” stand in for all the non-identified, no-named enslaved Africans who were part of the Dutch ships – Silence.

The Zikinzá ethnographic collection4 is the location of my third confrontation with silence. This collection of Afro-Curaçaoan legends, stories, and songs does hold those voices and experiences that I am eager to resonate with. Tales and melodies were passed down generationally and these recordings offer them through the voices of the descendants of enslaved peoples. Even here the silences are deafening as song lyrics are partly sung in a Papiamentu/o precursor that I do not understand or melodies and lyrics are transformed through time and oral transition from one generation to another. In this way, lyrical meanings remain mired in uncertainty and supposition.

Accounts on the lived experience of Black people are, according to Dionne Brand, collected as “random shards of history” (19). Archival work for Brand thus turns to “what was left—even if it is an old sack, threadbare with time” (94). As much as we have available, there is just as much silence and unknown, and so we work at “the limit of what cannot be known” as Saidyia Hartman describes it (4), arguing for a “writing at the limit of the unspeakable and the unknown” (1). Concentrating on percussionist and composer Vernon Chatlein’s work within the Zikinzá collection, I consider how music enables an interaction with encountered silences, and how (re)composing and performance allow us to sit and commune with “histories that hurt” (Ahmed 50). Music sounds out into the silence, it engages with the vast absence, speaking to the nonexistent that is nevertheless haunting, causing what Avery Gordon describes as ghostly hauntings, a “disturbed feeling that cannot be put away” (xvi). What do we do with the silences within this particular sound archive? How do we make sense of such silences personally and politically? How do we confront and rework them when our archival material is scanty and the little available is often illegible, comprising cut and disrupted stories, describing pasts that are at times incoherent and unfinished.

(Re)composing: Working in the Archive

For my people everywhere singing their slave songs

repeatedly: their dirges and their ditties and their blues

and jubilees, praying their prayers nightly to an

unknown god, bending their knees humbly to an

unseen power

—Margaret Walker 5

The Zikinzá collection is an audio collection comprised of 1,410 ethnographic recordings6 of singing, storytelling and rememberings of Afro-Curaçaoans recorded between 1958 and 1961. The ethnographic work of the collection was done by anthropologist and poet Elis Juliana (1927–2013) and missionary priest Pater P.H.F. (Paul) Brenneker (1912–1996) in Curaçao. This collection was registered by Unesco’s Memory of the World program7 in 2017 for its Documentary Heritage of the Enslaved people in the Dutch Caribbean and their Descendants (1830–1969). One recording from this archive, Bati Majo, will perform as an example through which I will discuss (re)composing and working within the archive.8

In (re)composing, Chatlein explicitly does not use the archive for samples, where one isolates and cuts a sound excerpt for use. Chatlein says “I am going to grab that whole track and work with that whole track … I am not going to cut and snip, when you do that you can make very beautiful shit, but the idea is to keep the voices as is … so you get the story of the person, of the people.”9 Using Ipads and sample pads, Chatlein mixes contemporary and antique technologies to sound out. Music software such as Logic Pro is used to join music and stories to create narrative. In this way, acoustic instruments and electronics come together in live performances. Effects are added to instruments such as acoustic guitar, piano, percussion, and vocals in addition to the voices of the archive. Different Caribbean rhythms and drums such as tambú, bata, and cajón are used, recognizing that the archive is Curaçaoan, but that making connection through the region is important for igniting spaces of dialogue and gathering.

Working with the entire recording Chatlein can interject in between the spaces of the drags and slurs of the archive voices. Chatlein’s intervention is minimal, laying chords that float under the voice, allowing it to take its role as the melody. There is disruption in the way Chatlein uses reverb to bring the voice closer or move it farther away, playing with its proximity. Reverb also gives resonance, with twists and turns the tone and timbre change. With unhurried tempos and well-timed phrases, Chatlein plays bata drums under and in between the voice.10

Audio Credit: Track 2 and Track 3 composed by Vernon Chatlein, and performed by Vernon Chatlein and Aki Spardaro.

(Re)imagining Silences: Putting Stories Next to Each Other

More silences. The names of Tula and Karpata, leaders of the 1795 uprising on Curaçao are not part of the recordings. Why are there no songs or stories about this event? There is documentation of a track (no. 612) with their names as title, but no audio account is available. Was this a story describing the revolt and uprising? Was music part of that revolt like those in Haiti at Bwa Kayiman? Were Tula and Karpata animated by drums? – Silence.

Though the silences that this archive embodies fund such unknowns and interpretative pitfalls, it also enables ways of (re)imagining new stories, futures, interpretations, and our own order of things. Working in this archive continuously (re)arranges knowledge structures, disrupting ways of thinking, including our own. Moreover, working sonically, listening again and again, unlocked my hearing of the stories and I could put them in relation to similar yet differing myths and stories I heard as a child growing up, but also during my research, such as those of flying Africans. The voices unmoor questions as I take a journey with Chatlein and the melodies sung and stories recounted about their ancestors’ experiences, about myths and the meanings they ascribed to music. On this journey we are guided by rhythm, sound, timbre, tone and effects. These sounds come out of our, as well as, their experience. (Re)imagining the unknown, we put our stories together and thereby stand in conversation with ancestors and each other.

Chatlein’s work sounds out “at the limit” (Hartman and Wilderson; Hartman) of the silence, not to fill it but to embrace it, in a sense, to be intimate with it. Such work exemplifies that music and ways of sounding out are living archives, and as such are reservoirs of (re)imagining practices, and can be empowering to listeners. In music we encounter one voice which opens possibilities to feel and respond to others by picking up that voice and elaborating on it, play with it, incorporate it; we can join each other. The presence of the ancestors’ voices is a sustaining force. Through such (re)compositions, music opens a transdisciplinary space to listen to, feel and examine the sounding out of the “afrospora” (Philip 45), claiming and freeing these voices that were and are often made to inhabit the border.

I conceive this way of (re)imagining in music as a response to the prevalent chorus about the silences and how they facilitate a space of non-history within the Caribbean. The doubt and suspicion aroused around Afro-Caribbean historicity are caused by the silences; but silence can be engaged with.11 Our active engagement with the sounds, melodies and lyrics, mostly towards a quest for self-knowledge, exemplify that such an archive warrants complication and further demarcation. The excavation involved in this work requires (re)imagining and reworking of Afro-Curaçaoan histories and experiences, and thereby creating a new archive that is in conversation with the silences and gaps of the extant one.

Working within this silence, occupying it, we can imagine, make our own narratives, ask what if? What does it take to? And what might it feel like to be? There is no remedy, material reparation or justice for expunged lives, historical and present trauma and colonial wounds. However, this space is rich in personal and collective meaning, especially where self-knowledge, -respect and -possession are concerned. It is important to acknowledge what is at stake personally in engaging with these voices from the past, especially within and against the bounds and limits of the archive and the silences it holds. Chatlein is building infrastructure for further listenings and readings of Afro-Curaçaoan past, present and future lived experiences.

Futurities

Let a new earth rise. Let another world be born. Let a

bloody peace be written in the sky. Let a second

generation full of courage issue forth; let a people

loving freedom come to growth. Let a beauty full of

healing and a strength of final clenching be the pulsing

in our spirits and our blood. Let the martial songs

be written, let the dirges disappear. Let a race of men now

rise and take control

—Margaret Walker12

Historically, Black lived experience and humanity have been unacknowledged and unremembered. This is part and parcel of the hurt that the saltwater passage brings (Smallwood). The haunting discussed at the beginning of this reflection is faced generationally; in my genealogical gaps for instance, in our structures of feeling, politics of pleasure and collective love-ethic. This haunting is continuously confronted in (non)fiction: from the ghost of a murdered baby that returns to terrorize 124 Bluestone Road (Morrison, Beloved) to the designed map to the doors of no return, through (re)imaginings of Zong (Philip; Sharpe; Saunders; Dabydeen; D’Aguiar), and the plantations that are burnt only to be rebuilt and set ablaze again.13 Turning to music, I have presented one possible response to how we might experience and interact with the silence encountered in the Black archive, and the Afro-Caribbean archive more specifically. The practice of (re)imagining has been a powerful means for connecting and communing with the past and the unknown.

Preliminary work done on this project has been personal and political. In our meetings and conversations, Chatlein and I grieve together in different spaces in the Netherlands. Wherever we meet, we mourn and celebrate. We stand in awe of the beauty that was made under constraint and listen together to vocal timbres, textures and melody lines, and try to work through the possible meanings of lyrics. Going through the feelings and emotions that arise is part of doing this work. We both acknowledge the heaviness of the archive, the injustice and terror of slavery and colonialism and the contemporary social, political, economic inequalities that are legacies of those past injustices. We are concerned about the future because of the precarity of our islands’ economic sovereignty. We are anxious and agitated by the current violent seizure and appropriation of land, cordoned off for high-rise hotels and to build military bases in order to wage war in the Global South. We fear the future implication of new and old forms of political and financial control as well as that of governmental organizations that exploit land and natural resources. However, at the end of each meeting about the Zinkinzá collection, we also recognize a lightness; a weight that is temporarily lifted while sitting amongst those voices – Listening.

Working with this archive we aim to make the collection relevant to people’s everyday lives, making the songs, stories and sounds part of that. Making it a collective community project, it can be alive as a source that promulgates everyday discussions and knowledges. The above can be put into action through community performance lectures and themed discussion series, online conferences and storytelling, and podcasts. It can enable active participation and communing with the voices. It also allows the archive to be spirited by different (re)imaginations. It can thus perform as a source of nourishment and healing. The aim here is to open a space for communing, where there is no soloist and we might be able to knit different voices together, including those of the archive; to question the archive and its political potential in our contemporary lived experience within the Dutch Kingdom. Space-making is critical to conversation having, especially where questions of liberation are concerned. This is a space in which we can (re)write, sing and dance alongside each other and ancestral voices. Communality can foster a space of knowledge and healing as we attend to each other, illustrating the rich potential of this archive in spite of its silences. Recomposing slave songs, using past experiences as a way to redress, to address, to question, to repair, we can imagine a different kind of possibility that is not rooted in trauma, but in continuous (re)imagining what it means to liberate ourselves in performance, in song, in melody, in music.