How to Hold an Image

Jue Yang

→

(Writer & Filmmaker)

How to hold an image? This is the question I asked in my performance lecture during the 2021 Inward Outward symposium: Emotion in the Archive. During my presentation, I held the images, both metaphorically and literally, from the 1927 film Inlansche Bedrijven by the Dutch filmmaker Willy Mullens. Here I describe some thoughts underlying my presentation:1

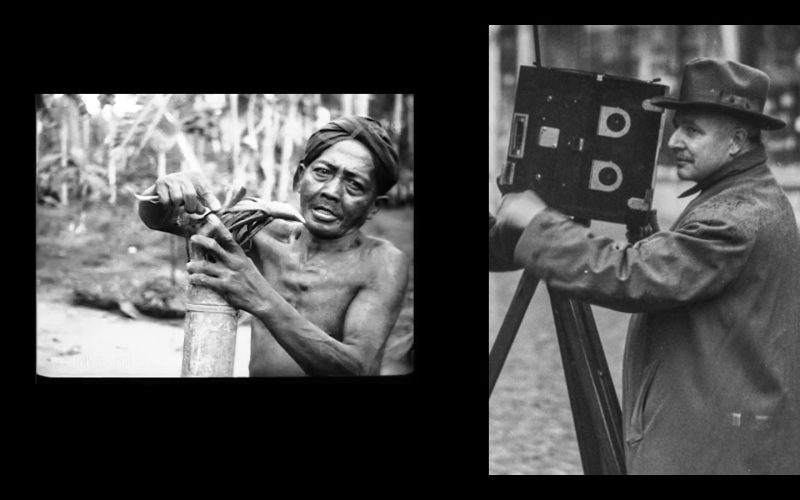

My first reaction towards the film is anger. What I see is a textbook example of crude, early ethnographic images that exoticise and objectify—and thus create—the Other. The colonial agenda of the film is clear, given that it was funded by, among others, the Ministry of Colonies and the Ministry of Education (Hogenkamp 20). As I watch the black-and-white footage from what was the Dutch East Indies, I notice the moments when people— women, men and children alike—look into the camera. Many of them seem timid. Some smile shyly and look confused. In my mind’s eye, I travel back to the filming site a hundred years ago where Mullens, supervised by two officials from the Education department (Hogenkamp 21), puts down his “big black box” in the middle of a village and, in a language they do not understand, directs people to re-enact labour.

While anger is my entry point into the film, I want to find ways to treat the images and their context with compassion. The biography of Mullens, to my surprise, becomes a generative space for contextualisation. In 1897, 17-year-old Mullens performed in the circus as a human cannonball. One evening he was knocked out by a kangaroo and failed to finish his act. The spectators booed, and Mullens was fired from the job (Koops). Both the objectification of the body as a cannonball and such amusement in a tragic event applaud violence and cruelty.

For the presentation, I decided to collage the scene where the villager, the camera and the human-cannonball-turned-filmmaker encounter each other. In this collage, I try to embody the gaze and locate the camera in its historical context. The Othering and objectification at the heart of colonial film-making cannot be compared or equated to the humiliation and objectification of human-cannonballing. Yet, by juxtaposing these images, I want to convey how Mullens saw his filmic subjects with a gaze that echoes the one he was himself subjected to. The movie camera, invented in the same decade as Mullens’ circus career (Martín), embodies the logic of power and alienation.

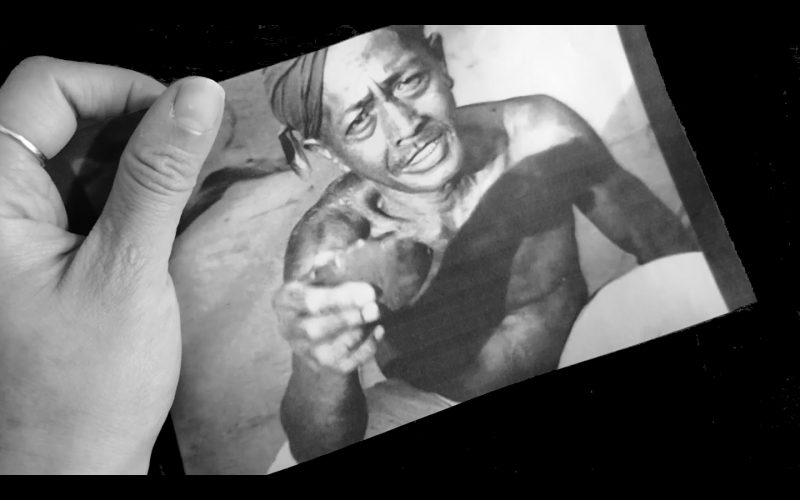

In the performance, I portray myself holding a printout of the villager. The image, screenshotted and printed on a piece of paper, becomes malleable and welcomes questioning. I narrate: “I want to knock on the image, shake it until it breaks open, tear it up and toss it until it comes screaming: no! But isn’t that itself a violent act—to break open the image and throw it away?” To hold an image is to go beyond seeing, to give rise to questions and pauses and, as I present in the performance lecture, to blur, interrupt, disrupt, replace the (colonial) gaze. Mark Sealy’s words serve as a productive proposition for me:

Decolonising the photographic image is an act of unburdening it from the assumed, normative, hegemonic, colonial conditions present consciously or unconsciously in the moment of its original making and in its readings and displays. Decolonising the camera is therefore a process of locating the primary conditions of a racialised photograph’s coloniality and as such it works within a form of Black cultural politics to destabilise the conditions, receptions and processes of Othering a subject within the history of photography. (Sealy 4)

I also created a video that shows my hand interacting with the film as it plays. I use an AI voiceover to tell an alternative version of the encounter between the villager and Mullens. The voice is based on a white male, which I use to ‘subjectify’ Mullens’ internal monologue.

I must note that these image manipulations are possible because the film is available online and that the Eye Filmmuseum agreed to the publication of the still and modified images. On the one hand, the internet that I encounter today offers prompts for methodologies of engagement with archival images—pausing, isolating and remixing images has become a norm. On the other hand, the unmediated availability of these images comes with its own problems. Such access can lead to an act of display without a critical premise or con textualized understanding, which perpetuates and obscures the coloniality embodied by the images.

In this short film, I hold parts of the archive film and tell an alternative story. Credit: Jue Yang. Archive film footage from “Inlansche Bedrijven”. Collection Eye Filmmuseum, the Netherlands.

When images are unlocked from glass cabinets and institutional screens—i.e. when confabulation becomes possible—one must be willing to acknowledge and reconcile with difficult history. In a way, to ask “how to hold an image” is to enquire: how to confabulate a story that counters the story told by the camera with the ethics of understanding and compassion?