Dreaming in Public

Aylin Kuryel

→

(University of Amsterdam, Literary and Cultural Analysis Department)

What are the different ways we can approach the “work” we do while asleep, and treat dreams as stories that can be shared, circulated, and stored, keeping the record of the past and the present as letters from and to the future? How can we attend to the ways dreams reflect collective experiences, thoughts, predicaments, desires, and anxieties—and attend not only to what they say about the ones who dream but about the realities that the dreamers inhabit? With these questions in mind, I have been collecting dreams in different

periods and have worked with them in diverse forms. I started by collecting people’s dreams about obligatory military service in Turkey (for people who are assigned male at birth). I continued, collecting dreams about the Gezi resistance in 2013 and then dreams about the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 in Turkey. I made short documentary films based on these sound pieces, trying to make dreams meet on the filmic surface in different forms, talking to each other through sound and image. I explored how dreams, when woven into each other, can turn into larger narratives that unwrap the affective patterns and shared memories of particular periods and contexts. Inspired by Ismail Kadare’s 1981 novel The Palace of Dreams,1 I wanted to attend to how dreams can cease being personal and become a public archive of collective responses to repressive realities.

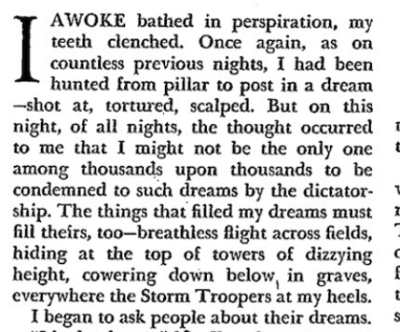

While making the documentary The Balcony and Our Dreams about pandemic dreams, I was engrossed by recurrent themes: masks, injections, hospitals, disquietingly approaching bodies, and forbidden kisses—but also zombies, German occupiers, police violence, assassinations, coup d’états, and surveilling politicians. Shared memories of political resistance and state oppression seemed to surface through the disorientation and disturbance generated by this global health crisis. In this period, I encountered a book I could not have even dreamt existed: The Third Reich of Dreams: The Nightmares of a Nation 1933–1939. Written by Charlotte Beradt (1966), a Berlin-based Jewish journalist, the book consists of dreams collected by Beradt under the Nazi regime, through which she explores the relationship between war, fascism, and dreams. Beradt explains how she came to the idea as follows (33–37):

Beradt collected almost three hundred dreams between 1933 and 1939, mostly from the people around her, such as her hairdresser, neighbors, doctor, milkman, friends, and family. She first hid the record of these dreams in her house, then later sent them by mail to friends living outside of Germany. She eventually fled to New York, where she entered an exile community that included Hannah Arendt, who helped her publish a collection of the dreams in 1966 (Sliwinski). In my imaginary library of dream-texts, this book finds its place next to the dreams of Walter Benjamin, who described one of his dreams in a letter he sent from an internment camp, and the dreams of Theodor Adorno, who recorded his dreams in the same dark period.

Daringly collecting dreams in a period where people dream that even dreaming is forbidden, Beradt’s book offers great insights into how fascism can sneak into our daily lives and shape how we think and how we relate to the world and to each other. They reveal fears, anxieties, feelings of isolation, disorientation, predicaments, and predictions, but they also open up a space to reflect on them.

Let us consider Beradt’s words again:

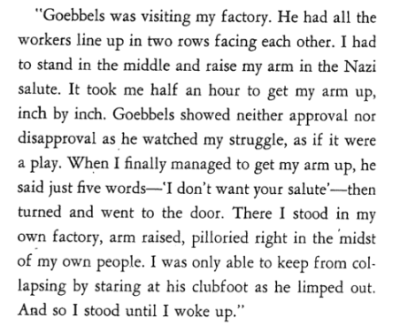

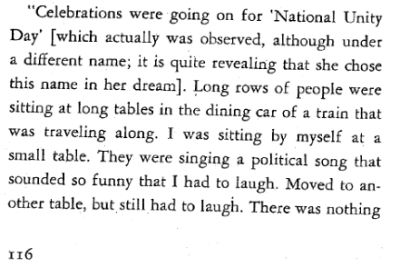

In the first pages of Beradt’s book, she quotes Robert Ley, a high-ranking administrator in the Nazi regime: “The only person in Germany who still leads a private life is the person who sleeps” (3). The Third Reich of Dreams proves the inaccuracy of this quote on every page, reminding us that people who sleep are not alone, and that sleeping is part of public life. Politics haunts sleepers, and all

dreams are dreamt in a context; they grow in fertile soil. Some dreams are, in Beradt’s words, “dictated by the dictatorship,” reflecting how people become complicit and internalize power in varying degrees, while other dreams provide the arsenal “to describe the structure of a reality that was just on the verge of becoming a nightmare” (9). Others are dreams of resistance, trying to find ways to get away, fight, and act together.

Let us read one of these dreams (5).

And another one (116).

One of the most remarkable and terrifying aspects Beradt identifies in dreams is that some images appear in dreams before they even happen in reality: people dream about mass displacements and concentration camps before they become reality; people dream they perish at the borders, lose their passports, forget their native tongue, and are subjected to torture in the places they migrate to before these things happen. In this sense, dreams appear as letters both from and to the future, as spaces of interpretation, prediction, action. This is why Beradt comes to see them as warnings that can help detect totalitarian tendencies and practices, the future of wars, at times signaling that the worst is yet to come.

Maybe not all these dreams are stories of survival, nor are they stories of survivors, but they are definitely stories that survived. They open up a space to share anticipations, experiences, and even tactics. Dreams resist forgetting; they archive past, present, and possible future atrocities, offering ways to share how we are broken. An archive that manifests how political violence penetrates into daily lives, everyday spaces, bedrooms, and sleeps; and how our stories are part of a larger history, experienced collectively. Meeting in dream-spaces is meeting in spaces of intimacy, which requires patience, at times generating discomfort and boredom, other times the joy of chance encounters. These are spaces of sharing, especially in dark times when public thoughts and bodies are increasingly restricted by openly fascist or neoliberal capitalist regimes that employ comparable forms of violence.

I see Beradt’s collection as a form of resistance, storing, shipping, and publishing dreams, making them meet and talk to each other, collaborating to tell the stories of fascism.

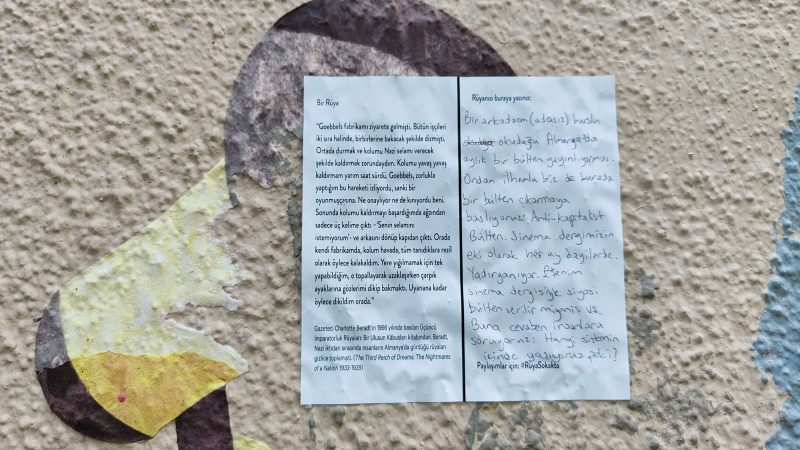

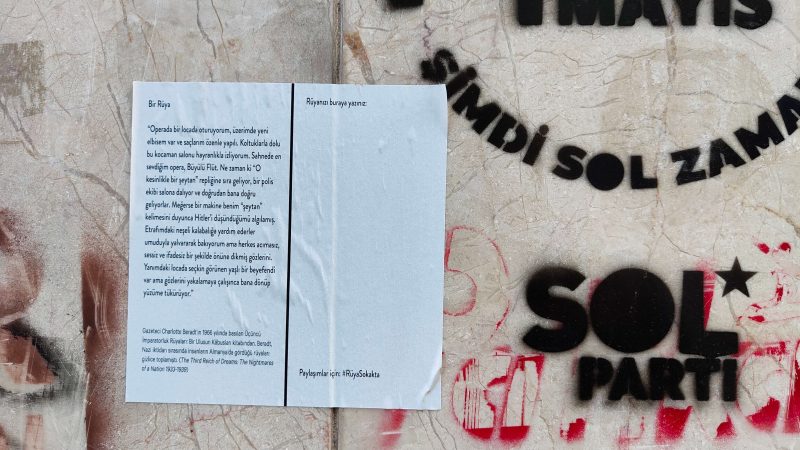

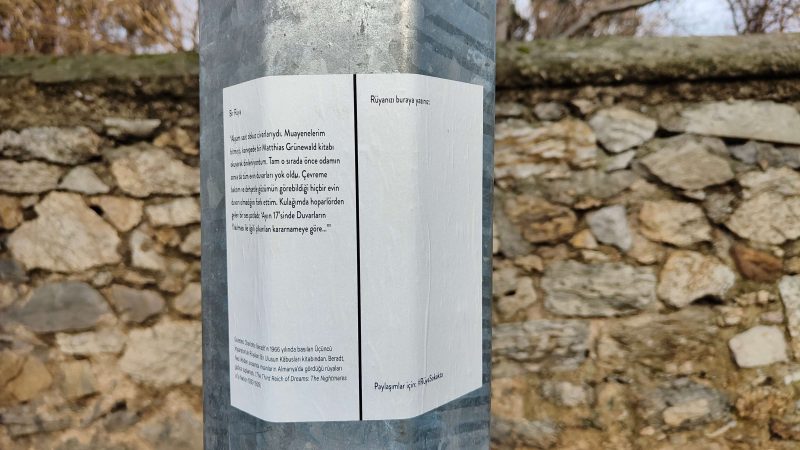

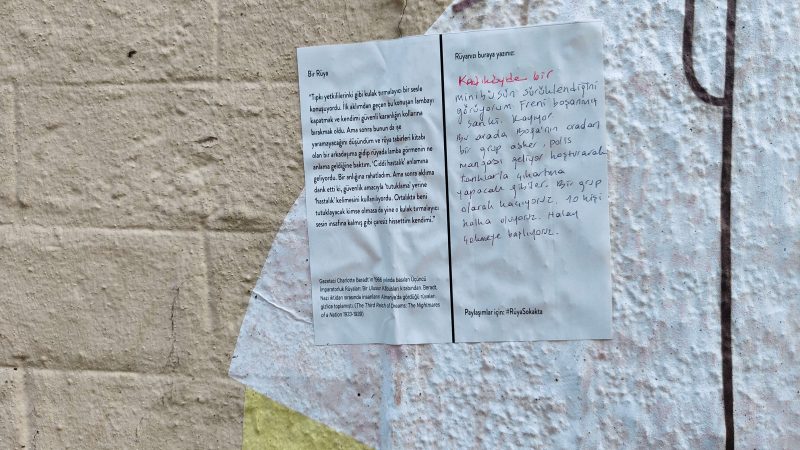

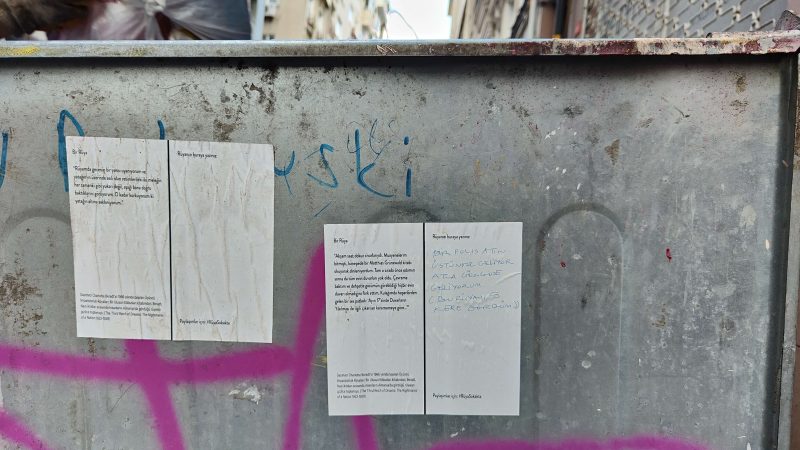

I wondered how dreams under Nazi Germany would resonate with dreams under the current authoritarian regime of Turkey. I asked myself: How to carve out a space in which dreams—or perhaps nightmares—of the past resonate with those of today? How to expand the dream-archive by making them talk to each other in a way that manifests how bodies and emotions are mobilized and violated in similar manners throughout history? How to confuse the assumed spaces of private and public in rethinking collective forms of repair? So I translated some of the dreams in Beradt’s book into Turkish and prepared stickers, divided into two, where one side contained the dream from The Third Reich of Dreams and the other side was left empty, inviting people to write down their own dreams. I put these stickers up on public walls in Istanbul. Some were filled in with handwritten dreams; some were left empty; most were eventually soaked in rain and torn apart.

I finish with two examples of people who went to bed and fell asleep under varying degrees of violence, oppression, and surveillance in different moments of history, speaking to each other to “meet in dreams.”

his dream for 5 times : ) )”