Decolonizing Archives in the Digital Age

Sebastian Jackson

→

(Harvard University)

Decolonization, according to Gĩkũyũ essayist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, is a project of decentering Europe in relation to the rest of the world, and of recentering the myriad ways of being human which were marginalized under the political, economic, and cultural hegemony of European modernity (Mbembe). Decolonization is also about disputing, disrupting, and dispensing with the specious assumption that European (i.e. white) and masculinist epistemologies—or regimes of knowledge and modes of reasoning—stand in for universal, objective “Truths.” That is, truths about the human condition, and about the ontological realities of the cosmos more generally. Epistemic decolonization was not realized with the formal independence of the colonized world during the second half of the twentieth century, and the afterlives of its racist absurdities and violent contradictions remain yet unresolved. The struggle for the decolonization of knowledge, too, is ongoing. South Africa, which did not achieve democratic emancipation from white minority rule until the early 1990s, has only recently begun to take on the monumental task of decentering the symbolic power of whiteness, which remains deeply embedded in public spaces, institutions, and culture. Yet, there has also been a concerted effort to “recenter Africa” in public culture (Mbembe). In recent years, student protests have begun to transform university campuses—bastions of whiteness, centers for the production of colonial knowledge. They have torn down old monuments and erected new icons in the wake of the #RhodesMustFall movement; they have insisted on providing impoverished African students access to affordable education; and, they argued forcefully for the diversification (or Africanization) of curricula, administrators, academic faculty and staff, and the languages of instruction.

The decentering of whiteness in post-apartheid society requires a thorough reexamination of history and collective memory, for it is precisely through willful forgetting and denial, cultural amnesia or aphasia, and assumptions of innocence that colonial forms of whiteness continue to entrench themselves (Stoler, “Colonial Aphasia”; Wekker). But are institutional archives, and the academic disciplines concerned with knowledge production, not also implicated in the legacies of European colonialism? They most certainly are. One cannot deny that nineteenth century anthropology—with its unyielding obsession with cultural and biological difference—made ample contribution to the invention of race as a category of human “otherness.” Nor should we forget that anthropology’s mandate to study the so-called “savage”—to paraphrase Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot (7–28)—helped facilitate the discursive construction of the “civilizing mission” and the “white man’s burden,” lending credence and legitimacy to the political projects of racial subordination and colonial domination (Apter; Pierre). But then, a critical and historical anthropology, based on experimental ethnographic and archival methods, and which is rooted in a decidedly postcolonial, anti-racist, and feminist politics, is also well-positioned to examine and unpack the historical genealogy of racialized discourses and practices. Such a critical anthropology, which does not take disciplinary boundaries or its orthodoxies too seriously, can bring to light certain theories, practices, and strategies which call into question the socio-symbolic salience of whiteness and its undertones of superiority (Stoler, “Rethinking”; Thomas and Clarke; Mullings).

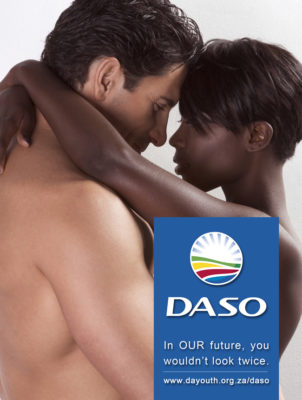

My own research explores the social and political mechanisms by which sexuality, desire, and intimacy were politicized and racialized under slavery, colonialism, and apartheid rule. However, it also examines the different ways in which people actively blur and unmake racial boundaries and distinctions, and how they participate in the decolonization of intimacy in the contemporary moment. In particular, my project examines the social and cultural legacies of South Africa’s so-called “Immorality Laws” (Ontugwet), which prohibited and stigmatized marriages and sexual relations between all “Europeans and non-Europeans” in order to maintain the “purity” of whiteness and the boundaries of rule. These anti-miscegenation laws were first implemented in 1927, but reflected much older social norms and relations rooted in slavery. Under the sway of the Immorality Laws, mixed (gemengde) couples—such as this pair from Johannesburg pictured on the next page in the 1940s—were deemed enemies of the state, and were subjected to incessant surveillance, police harassment, incarceration, and public humiliation.

“Mixed” or “coloured” children born from illicit interracial unions were rendered illegitimate, shameful, and tragic (Erasmus; Adhikari; Mafe). These Immorality Laws developed as the cornerstone of apartheid policy, and in 1968, were expanded to include same-sex intimacies as well (Hoad). Judith Butler (quoted in Graham 12) rightly argues that anti-miscegenation laws were not only violent because they prohibited interracial sex, they also ensured the discursive and political foreclosure of possibilities for intimacy and love, in the sense that it became socially unthinkable to desire the Other. Ultimately, though, desire is unruly and ungovernable, and the political repression of desire often produced the very same desires it sought to foreclose. Given their inefficacy, these laws were finally repealed in 1985 (Klaussen).

I employ mixed methods in my research, which include visiting institutional archives and sifting through files, wandering through museums, doing participant observation research in public spaces, conducting semi-structured interviews, and reading novels. I also study contemporary debates about race and intimacy in public culture by analyzing TV shows, listening to talk radio, and following social media trends. I study how these debates are contested and represented in visual culture, and how images, films, advertisements, and other aesthetic forms actually intervene in the process of decolonizing the collective imagination, as South Africans endeavor towards the building of a “Rainbow Nation” from the ruins of apartheid. I first began my ethnographic and historical study of apartheid and post-apartheid society in early 2012, when I spent a semester at Stellenbosch University—the historical stronghold of Afrikaner nationalism and apartheid philosophy—as a visiting international student. I came across the campaign poster pictured below, which was plastered to a pillar near the front entrance of the library.

The poster caught my attention because it seemed rather out of place on the university’s predominately white and Afrikaans-speaking campus. I later learned that the youth wing of the Democratic Alliance, an important opposition party, distributed this campaign poster around university campuses across South Africa. The poster depicted a mixed couple and was displayed in public spaces. It sparked a storm of controversy and was debated on digital and print media for weeks (see Vincent & Howell). The vitriol with which conservative critics reacted, suggested that the liberal dream of a “nonracial” or “postracial” South Africa had not yet arrived (Goldberg).

Although traditional methodologies, based on “going to the archive” and making ethnographic observations by “being there” remain indispensable to critical social analysis, there is also a need to reimagine how we do participant observation and archival work. It is incumbent on us all to reconceptualize what archives are, what work they do, and how we may access them. The need for a thorough reconceptualization of archival research has, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, never been more urgent. Luckily, South African institutions and organizations have been digitizing their collections since the late 1990s—very much in the spirit of decolonization and democratization. Digital archiving organizations, such as Digital Innovation South Africa (DISA), have made its resources digitally available to all—allowing me to continue plumbing its files for texts and images, from the safety of my home in the United States.

I am particularly interested in studying photographic images, films, and other visual representations which circulate digitally, because public debates regarding intimacy and racial identity in contemporary South Africa largely unfold in digital spaces. Decolonizing the archive is largely about what Achille Mbembe calls the “democratization of access,” about making the retrieval of historical memory more easily and widely accessible, especially to historically marginalized people. Accessing official archives often requires special permissions, which are not always easy to obtain; they tend to be highly centralized and bureaucratic, and the bureaucratization of memory-work tends to follow the mandate of some official discourse or another, some sanctioned version of history or another. What is included and excluded in archives such as these is not happenstance but reflects the political priorities of states and other institutions. Digital repositories are certainly more accessible, and do not always follow the same organizational logic as traditional archives; they allow for texts and images to be accessed from just about anywhere. For example, YouTube and Google Images do not necessarily rely on professional bureaucrats and archivists at all. Moreover, such platforms allow scholars, artists, and other interested persons to participate more fully in the cultivation of our collective memories and histories.

While we should explore the various kinds of archives that have emerged in recent decades, it is also of import that we consider emerging theories of archiving, that we reconsider how archives function, and that we reimagine their productive possibilities in the ongoing struggle to decolonize knowledge. Towards that end, I want to focus on three particular ways of thinking about archives. Archives are collections and repositories of information which are more or less organized, and which can reveal a great deal about the memories, representations, and identities of the people and communities to which they pertain. Edward Said’s concept of the “cultural archive,” which I first encountered in Gloria Wekker’s work on “white innocence” in the Netherlands (2), is important because it speaks to the historical sedimentation of cultural beliefs and attitudes—the deep structures of feelings and thought—which constitute a society’s “common sense” about itself, and which becomes manifest in everyday interactions and people’s lived experiences. Secondly, I want to mention a similar concept, namely that of the “shadow archive,” from the work of photography theorist Allan Sekula, which refers to an “all-inclusive archive” which “necessarily contains both the traces of the visible bodies of heroes, leaders, moral exemplars, celebrities, and those of the poor, the diseased, the insane, the nonwhite, the female, and all other embodiments of the unworthy” (10). This concept refers to the social production of images, which accumulate as a vast but disorderly storehouse of hidden histories and long-lost memories. This brings me to the third concept, namely John and Jean Comaroff’s proposition that we not only “go to the archive,” but also that we build and collect archives of our own. Considering the expansive capacities of digital media in the contemporary world, opportunities for reimagining decolonial forms of memory-work and history-making have become bountiful and boundless.