Curating the White Fathers Film Collection

Brecht Declercq

→

(meemoo, Flemish Institute for Archiving)

Jonas van Mulder

→

(KADOC–KU Leuven)

The film collection of the Society of the Missionaries of Africa (commonly known as the White Fathers) is the only audiovisual collection included in the Belgian Flemish List of Precious Heritage. It consists of 954 objects as sound (in multiple languages), image (all in 16mm), and combined reels, which together constitute 80 different content entities. These are mainly mission films from 1948–1960 and mainly shot in what today is the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, and Burundi. The collection is still owned by the White Fathers, but deposited at and preserved by KADOC, the interfaculty Documentation and Research Centre on Religion, Culture and Society at the KU Leuven. In 2019–2020 meemoo, the Flemish Institute for Archives, in collaboration with KADOC–KU Leuven, the Royal Belgian Film Archive, and with the support of the Flemish Government coordinated its analogue restoration and digitization. The total collection held many copies and versions of the same material, such as black-and-white and colour versions, shorter edits, etc. The 202 best preserved elements that remained as close as possible to the original negative, constituting together the most complete versions, were chosen for restoration and digitization. If multiple language versions were available, the African language version and the Dutch and French versions were digitized (technical details below).

The White Fathers film collection, especially given this digitization project, offers a particularly valuable and significant opportunity for collaboration between heritage institutions and heritage communities, though White Fathers films have already been part of initiatives in the past, most notably the project Mémoire filmée de la période coloniale, a collaboration between the Royal Belgian Film Archive, AfricaMuseum, KADOC-KU Leuven, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Université Saint-Louis Bruxelles, Université de Kinshasa, Université du Rwanda, and Université du Burundi (Etambala and Van Schuylenbergh). The argument set out in this essay is that venturing into new collaborative or restitution projects involving White Fathers films requires an accurate understanding of the particular character of their filmmaking. The following essentially takes up the question of the (possible) perpetuation of postcolonial, paternalistic approaches to “African culture” through heritage initiatives that engage with colonial sources. When can the exchange of digitized sources from colonial contexts between Western heritage institutions and heritage communities be considered an effective form of restitution and an avenue for postcolonial reparation, and when does it risk becoming an expression of technocratic paternalism and symptomatic of persistent (post)colonial inequalities? While this essay cannot, of course, aspire to offer a way out of this complex conundrum, it does seek to contextualize the issue within a specific historical and archival context.

The White Fathers film productions should be seen in the light of the post-war context of Belgian colonial and missionary film. As early as the 1920s, Catholic CICM missionaries were screening films in Léopoldville (Kinshasa) and Salesians and Benedictines were using cinema in Elisabethville (Lubumbashi). By the 1930s, the use of film technologies was widespread among missionary congregations active throughout the Belgian colony (Vints, “Beeld van een zending” 381–387). At the same time, native spectatorship remained very limited due to the segregation between white quarters and Black townships and a legal prohibition for Congolese to attend screenings of colonial or commercial films. In reality, however, it was impossible to prevent local people from watching films, and by the end of World War II, Belgian colonial policies became more lenient regarding native film consumption, eventually allowing for the emergence of colonial film productions made specifically for local audiences (Kapanga 254–256).

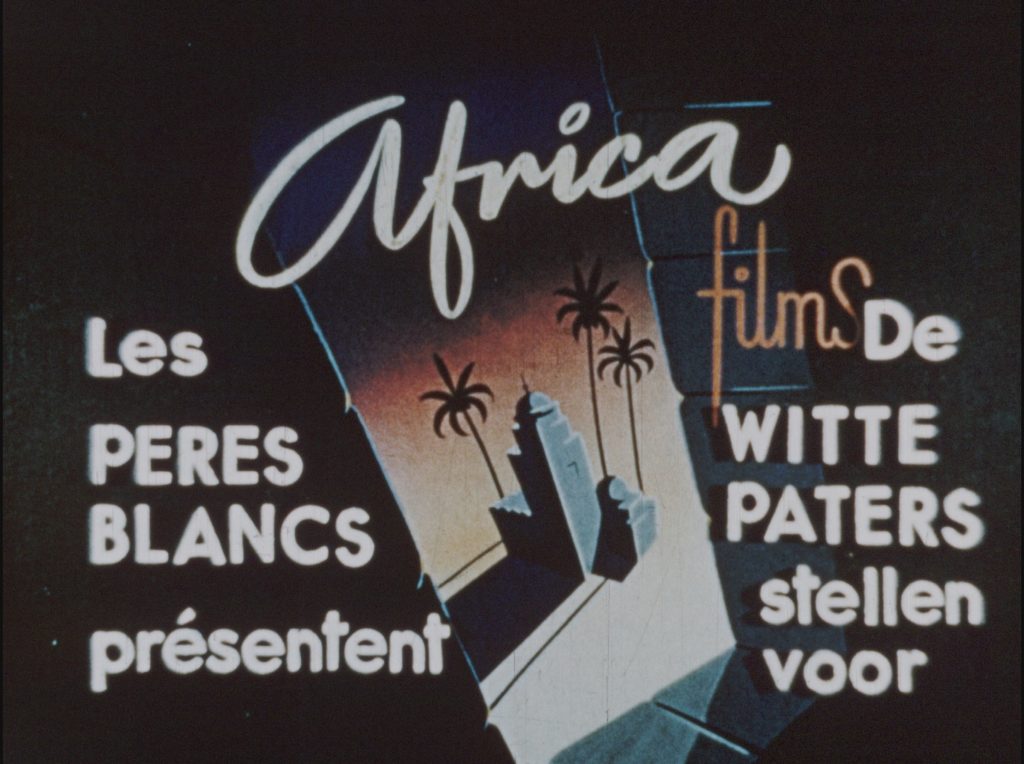

A significant portion of the films that specifically addressed local audiences was created by newly founded missionary film production companies. The Congolese Centre for Catholic Action Cinema was inaugurated in 1946, arising from the efforts of Catholic missionaries to allow cinema to be used for religious propaganda, fundraising, and evangelization. There were three major film production centers in the Belgian Congo: Edisco-Films in Léopoldville (Kinshasa) and Luluafilms in Luluabourg (Kananga), both managed by CICM missionaries, and Africa Films, stationed in Bukavu and Kivu and headed by the White Fathers (Diawara 14). The upsurge of homegrown missionary film productions was paired with a condescending and moralizing attitude towards native spectatorship. Colonial and missionary filmmakers clang to the notion that natives needed to be taught how to watch moving images, and hence productions had to follow principles of simplicity and visual continuity—although it must be said that this pedantic approach was, at that time, also applied to film audiences in Belgium (Vints, “Kerk en film” 16–17). One of the epitomes of paternalizing native viewers is Les Palabres de Mboloko, a series of 16mm colour animations from the 1950s created by the CICM missionary Alexander van den Heuvel; cartoons tailored for adult natives who were considered too immature to process feature films. Ch. Didier Gondola keenly observed that missionary filmmaking thus reproduced the inherent contradictions of Belgian colonialism, which trumpeted its own transformative prowess yet accommodated an immutable view of Africa and Africans (54).

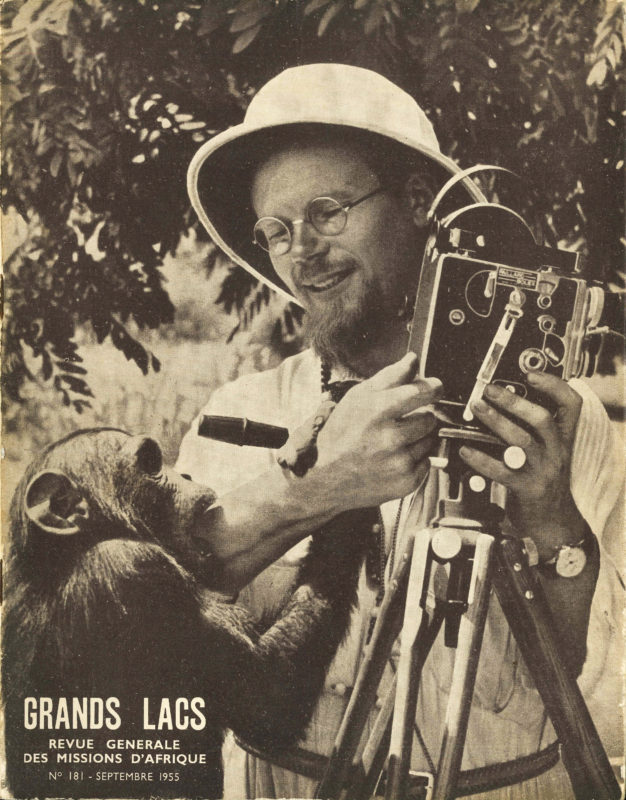

Despite revealing recent work, historians of colonial film still struggle to find tangible evidence of how precisely local audiences reacted to screenings of missionary and colonial films, how precisely they were “taught” to watch films, and how local actors were cast (Reynolds; Rice). While the digitization of the White Fathers films will provide an unprecedented rich source for new explorations in the history of missionary and colonial film, a great deal of background information can be gained from both published and unpublished sources related to their production and consumption. Periodicals published by the White Fathers often dealt with the topic of cinema and sometimes published testimonies of missionary filmmakers sharing background information about the production process. Likewise, the archives of Africa Films, preserved at KADOC-KU Leuven, contain documents such as scenario preparations, correspondences and administrative documents that give direct or indirect information about the objectives, the rationale and the creation process of these movies. This “paper trail” will be a crucial resource to understand and anatomize the visual and narrative strategies of White Fathers as screenwriters and directors. Interestingly, they show several instances of discussions of ethical issues. For example, in 1965 Africa Films received a request from the New York-based film production company Explorers International Films to use fragments of White Fathers films for the completion of “a film on primitive people around the world.” Replying to this inquiry, John Bell, representative of the White Fathers in Washington D.C, points out that the missionaries have a “moral commitment towards the Africans who have collaborated with them in film productions” (Bell). And when in 1949 White Father Antoon Van Overschelde received feedback from French confrères on a scenario for a new film, he is cautioned “not to slip into grotesque stereotypes similar to those used to portray Afro-Americans in early twentieth-century American film” (Masson). While expressions and comments such as these are still very much couched in a paternalist discourse—the African actors and spectators remain excluded from these conversations—closer examination will surely yield more elements that together reveal a much more complex and nuanced reality behind the scenes than one would suspect based on the stereotypical representations pervading the films themselves.

Curating the White Fathers film collection adds another layer of complexity to current discussions regarding digital restitution of audiovisual sources from colonial times. Like other missionary filmmakers, White Fathers screenwriters and filmmakers were fully sympathetic to the adage that Africans needed films tailored to their supposed capacities as a film audience—“Il faut aux Africains des films africains.” The 1955 issue of the White Fathers periodical Grands Lacs shows precisely how profound missionaries considered the contribution of their films to be for native spectators. An article on missionary films for the Congolese states that it is the responsibility of missionaries to “respect, to capture and to preserve the richness of African culture,” and this in order to “return these treasures to the indigenous spirit” (Heuvel). The idea expressed here is that missionary filmmaking was salvaging age-old rituals, legends, and imageries from the cultural clear-cut brought about by Western modernity, echoing the conviction originated in nineteenth-century colonial ethnography that fieldwork and the collection of artifacts and audiovisual documentation could redeem Indigenous communities threatened with cultural extinction caused by cultural change imposed on them by colonization and global capitalism. Through their films, missionaries argued, decaying native traditions could be “restituted” (“restitué”) to local audiences. Cinema is thus attributed with the ability to lead native people back (“reconduire”) to their own cultural identity and their “patrimoine spirituel” (Heuvel).

Whether the exchange of digitized colonial sources between heritage communities can be considered an effective form of restitution, or should be seen as yet another expression of a technocratic paternalism symptomatic of persistent (post)colonial inequalities, is the subject of ongoing debate in heritage and archival studies. The paradox of the idea of the “authentic African film” produced by European missionaries calls for reflection about the extent to which this narrative might also covertly resonate in digital sharing and other forms of “restituting” audiovisual archives from colonial times by heritage institutions in the West. A combined critical disclosure of film and documentary archives, both of which cannot happen but with the consent of representatives of the White Fathers and involving all relevant communities and their representatives in DR Congo, Rwanda and Burundi, might avoid the risk of unwittingly reproducing precisely those historical dynamics that ought to be remedied in the future.

__

Restoration and Digitization Technical Details

For the master files, meemoo opted for common, widely accepted and sustain- able file formats: DPX, 10-bit logarithmic in RGB without colour subsampling on a 2K resolution (2048 x 1556). The sound was stored in 24-bit, 48kHz LPCM-cod- ed WAV files. From these master files a mezzanine copy with limited colour correction was created in Apple ProRes (normal, variable bit rate), with a 4:2:2 colour coding, at 25 fps in full HD (1920 x 1080), with pillar boxing or letterbox- ing applied if necessary to retain the original analogue film resolution and the sound in 24-bit, 48 kHz. The digitization was executed at R3Store Studios in London on a DFT Scanity film scanner from November 2019 until April 2020, by Nathan Leaman Hill and Gerry Gedge and supervised by Jo Griffin.